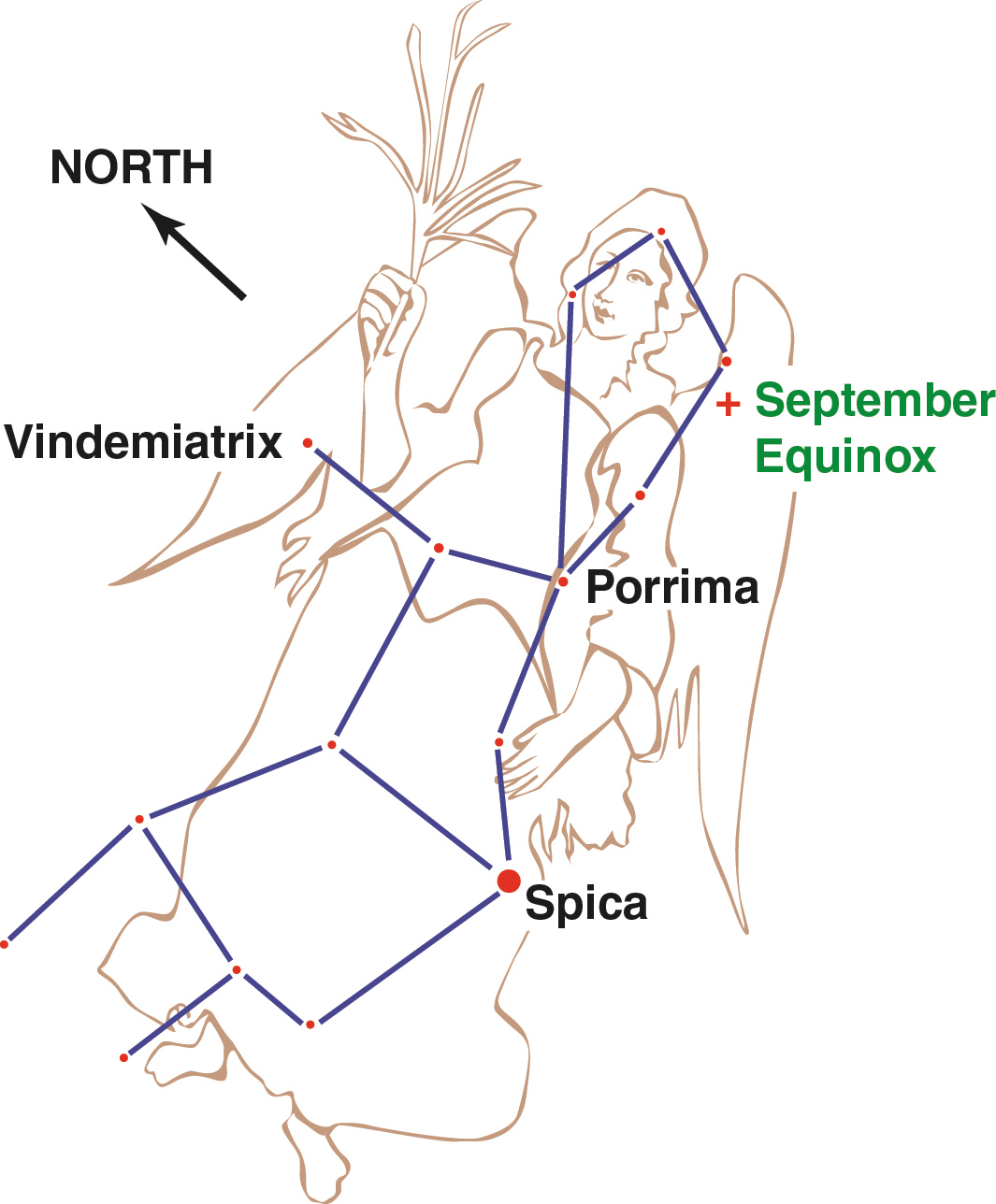

In mythology, Virgo was associated with the harvest. It represented a harvest goddess or the daughter of a goddess. The constellation’s brightest star, Spica, was a stalk of wheat held in her hand. Virgo was associated with the harvest because the Sun passed across the constellation during late summer or early autumn, when farmers were reaping the crops they had planted months earlier.

Virgo is known as a spring constellation because, although you can see some or all of its stars on most nights of the year, the stars put on their best display in the evening sky during spring.

Although blue-white Spica is Virgo’s only bright star, it is the 16th-brightest star in the night sky. It actually consists of two stars, both of which are much hotter, brighter, and heavier than the Sun. But they are separated by only about 10 million miles, so from Spica’s distance of 260 light-years, it is impossible to see them as individual stars.

Because the stars are big, heavy, and close together, they exert such a strong gravitational tug on each other that each star causes the other to bulge outward. Seen in profile, the system would look like two eggs with the narrow ends pointed at each other.

In the next few million years, the heavier star will near the end of its “normal” lifetime, so it will puff up to many times its current size. As it swells, some of its gas will begin to dump onto the surface of the other star. And as it gets even bigger, its outer layers will engulf its partner, pulling the two stellar cores closer together. No one knows exactly how the scenario will play out after that. The stars may merge to form a single star, or the larger star may explode before that can happen, blasting itself to bits and perhaps sending its companion careening through the galaxy like a stellar bullet.

The second-brightest star in Virgo, Gamma Virginis, is also a binary system. Unlike Spica, its stars are so far apart that binoculars easily reveal them as individual stars. They are about 40 light-years from Earth. The stars are both white, which means their surfaces are a little hotter than the surface of the Sun. They’re both brighter than the Sun, too.

Gamma Virginis has been known by several other names over the centuries. One of the most enduring is Porrima, for the goddess of prophecy. In ancient Babylon, it was called Star of the Hero, and in China, it was the High Minister of State.

A few galaxies of the Virgo ClusterWhile Spica is the most prominent object in Virgo, the most interesting may be the Virgo Cluster — a collection of several thousand galaxies. It is centered about 60 million light-years away.

A few galaxies of the Virgo ClusterWhile Spica is the most prominent object in Virgo, the most interesting may be the Virgo Cluster — a collection of several thousand galaxies. It is centered about 60 million light-years away.

The cluster forms the largest structure in our region of the universe. The galaxies are bound to each other by their gravity, so they move through space together. The cluster exerts a strong tug on our own galaxy, the Milky Way, and the small band of galaxies that it’s bound to, the Local Group. The Local Group is being pulled toward the Virgo Cluster, and eventually may join it.

The largest member of the cluster is M87, which spans one million light-years and contains one trillion stars or more. It’s a type of galaxy known as a giant elliptical. It looks like a fat, fuzzy football. Its core is inhabited by one of the largest black holes yet discovered, a monster about 6.6 billion times the mass of the Sun.

At the other end of the distance scale, Virgo also is home to two of the closest star systems. But the stars are so puny that they are not visible to the unaided eye. One system, Ross 128, is less than 11 light-years away; only 10 known star systems are closer. The other, which a pair of stars known as Wolf 424, is just four light-years farther. Both stars are classified as red dwarfs. They are much less massive than the Sun, so they’re only about one ten-thousandth as bright. If any of these stars took the Sun’s place, daytime on Earth would be only a few times brighter than a night with a full Moon, and Earth would be an iceball, with no chance for life as we know it.