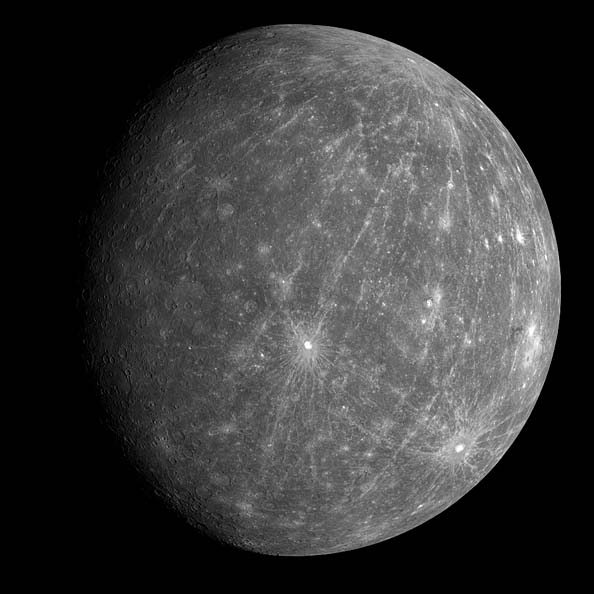

Mercury's surface closely resembles the Moon's. It is covered by impact craters, ancient lava flows, and quake fault lines. Mile-high cliffs stretch for hundreds of miles across the planet's surface. The huge Caloris impact basin, 800 miles (1,300 km) wide, decorates one side of the planet.

Mercury is only about six percent as massive as Earth, but it is about the same density. It is dominated by its iron core, which makes up 70 percent of its mass. The core may be partly molten, which would explain the presence of Mercury's weak magnetic field, which is just one percent as strong as Earth's. Above the core, Mercury has a thin mantle and crust.

A thin but strong wind from the Sun blasts particles off of Mercury's hard surface, creating a thin atmosphere around the planet. The particles rapidly escape into space, even as the never-ending solar wind blasts more material from the surface.

Mercury speeds around the Sun faster than any other planet. Its 88-day, highly elliptical orbit brings it within 29 million miles (47 million km) of the Sun, and then swings it out to 44 million miles (70 million km).

In the 1800s, astronomers realized that the physics of the day could not correctly predict Mercury's orbital path. The reason remained a mystery until 1915, when Albert Einstein used his new theory of gravity, General Relativity, to correctly predict Mercury's orbit — and explained the reason for previous errors: Mercury is so close to the Sun that its orbit is affected by the "warp" in space created by the Sun's powerful gravitational field.

From Earth, we view the same side of Mercury each time it passes closest to our planet. For a long time, this caused astronomers to think that the planet was tidally locked with the Sun — that is, its day and year were of equal length. Not so; in 1965, radar observations showed that Mercury completes three spins on its axis for every two orbits around the Sun.

The planet's surface swings through extremes of temperature. In the daytime, it can reach 700 degrees Fahrenheit (315 C). At night, the temperature drops to –300 F (–183 C). Radar observations suggest that water ice might inhabit shadowed craters at Mercury's poles. These regions never see the Sun, so the ice would not vaporize into space.

Mercury's distance and proximity to the Sun make it difficult to study with ground-based telescopes. It's visible only just after sunset or just before sunrise, forcing astronomers to view it through a thick, turbulent layer of Earth's atmosphere.